Improving incident investigations & safety systems

The NHS investigates around 10,000 Serious Incidents every year. That’s 10,000 cases of serious harm from which we have a duty to learn and a duty to improve.

When the Public Administration Select Committee reported on the quality of serious incident investigations in 2015 (Investigating Clinical Incidents in the NHS) they found that one of the most important things that has been learned from NHS incident investigations is that we need to do them better.

Window view into an operating theatre UK. Adrian Wressell CC-BY-4.0

The leading sources of healthcare harm are not simple technical failures such as a machine breaking down, or iatrogenic risk such as medication side effects. The ‘apparent’ leading source is the actions of people who go to work with the intention of providing safe and effective care. I have written ‘apparent’ because when a patient comes to harm it is – logically and statistically speaking – almost inevitable that one of the people providing care will have done or failed to do something. Person to person care is, after all, what clinical care is all about: a well person doing for an unwell person what the unwell person cannot do for themselves. But we need to look beyond the immediate apparent cause, and appreciate how the moment of harm is only the final step in a long chain of causation.

These chains of causation are complex and opaque. They can be better understood by adopting a systems-based perspective using knowledge of human factors and ergonomics. (See for example Carayon & Wood 2010) But this approach is not, for the most part, embedded in NHS incident investigations. The NHS’s new Patient Safety Incident Response Framework has mandated a shift towards more systemic investigations, which is a laudable development. However, it begs the question of where the expertise is going to come from to carry these out.

This post is about the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System. HFACS is a user-friendly, cost-effective and evidence-based approach to incident investigation, based on the goal of understanding organisational systems. It can also be used proactively to evaluate safety culture and safety management systems. In recent years I have worked with UK health providers in both the public and private sector to explore how HFACS can improve their investigations and the safety of their operations. I also benefited from a Churchill Fellowship to visit the US and Canada to find out more about how systems there were using both HFACS and human factors approaches to improve quality.

Introducing the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS)

Healthcare is a complex system where multiple interactions between people, technologies, and the physical environment create endless opportunities for things to go wrong. How can we protect patients from harm caused by human error? The science of human factors uses knowledge of how people behave in order to design safe, effective and efficient systems. But human factors specialists are thin on the ground in healthcare.

HFACS is a practical, tried-and-tested framework based on human factors. You do not need extensive expertise in human factors to use it. It helps investigators work systematically to identify and analyse the behaviours that are leading to harm. Used proactively, it can also help identify and reinforce the behaviours that are promoting safety.

HFACS was first developed for use in military aviation. However, US healthcare providers including the Mayo Clinic, the MD Anderson Cancer Centre, and Christus Health saw its benefits. They helped to adapt it so as to make it suitable for healthcare.

Behavioural scientists Scott Shappell and Douglas Wiegmann drew on James Reason’s famous ‘Swiss Cheese’ model of incident causation to develop HFACS. In Reason’s model, incidents are viewed as an outcome of wider organisational processes. They do not have a single ‘root cause’. Rather, they result from a combination of causal factors arising at different levels within the organisational system. Most of the time patients are kept safe by a combination of safety policies and systems, and intelligent adaptive action by people who see a risk and take steps to prevent it materialising. But sometimes, these defences fail. (There’s a bit about recent criticisms of Reason’s model at the end of this post…) This is a very simplified representation of the “Swiss Cheese” idea.

We are safe most of the time because the ‘holes’ in each ‘layer of defence’ are in a different place. (Image, HFACS Inc)

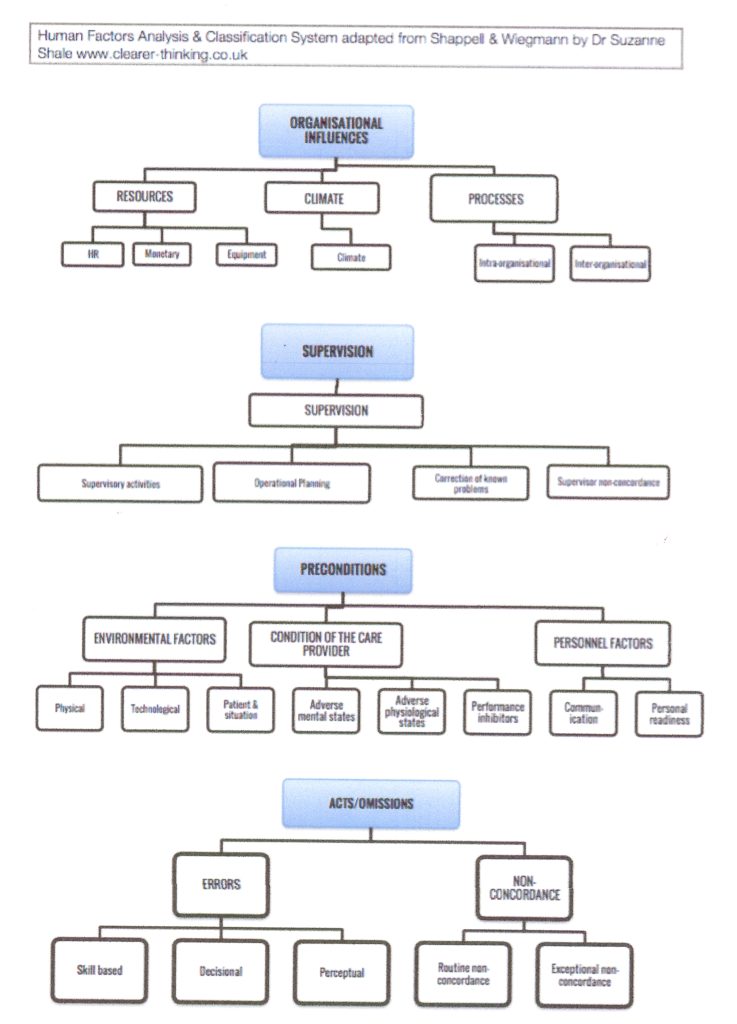

The not-very-pretty diagram that appears below the next paragraph shows the version of HFACS that I have developed for use in the UK. (It might look a bit complicated at first, but trust me – I’ve presented it to a wide range of audiences from peri-operative staff to senior leaders and they all get it pretty quickly. Even the leaders.)

HFACS groups types of human errors into into four organisational levels. Starting at the top, it identifies organisational influences, supervisory activity (clinical leadership and middle management), preconditions to front line activity, and finally front line activity itself. So the first important point is that HFACS guides investigators towards a ‘board to ward’, top-to-bottom analysis of incidents. HFACS then sets out categories and sub-categories for each of the levels. So the second important point is that investigators work systematically, because they are guided to look at all of the areas of an organisation’s activity where contributory factors may be found. Finally, in each category, ‘nanocodes’ prompt even novice investigators to look for specific types of human error characteristic of the context (such as failure to respond to reported concerns, or misperception of visual cues in operating theatre equipment). These categories, sub-categories and ‘nanocodes’ provide a stable structure for the analysis and comparison of incident findings across an organisation, between organisations, and over time. (The nano codes do not appear in the diagram)

Applying HFACS in UK healthcare

HFACS is already generating insights for the organisations that are working with me to implement it. A project with one provider flagged up significant deficiencies in their investigations into surgical ‘never events’, and the action plans that went with them. Another provider has found it valuable as a framework to review the safety culture of their operating theatres. Working with Murray Anderson Wallace and the East Midlands Academic Health Science Network we have been testing HFACS to excellent effect in mental and community healthcare. NHS providers are starting to use it to review and structure systems based investigations.

What are the most important messages to come out of this work so far? Well, there are several, and that’s for another post.

What are the problems with Root Cause Analysis as it’s being done?

My Churchill Fellowship report sets out the problems that have accompanied doing RCA in health care organisations, and why it doesn’t (and probably can’t) achieve its aims.

Healthcare providers in both the US and UK have invested huge amounts of time and money into investigating incidents using ‘traditional’ RCA. But the Public Administration Select Committee reported what a lot of people already suspected. Many so-called RCAs are not really RCAs, they’re just investigations. Many are of poor quality. And relying on RCAs to develop systemic responses to things that go wrong has not worked. Introducing HFACS doesn’t mean ditching everything you currently do and starting again. It means modifying and improving approaches to investigation.

So what is wrong with traditional RCAs, by comparison with HFACS?

- Unlike HFACS, an RCA process does not itself guide investigators towards optimal identification of risk events. How robust the RCA findings are, depends on the systems-safety knowledge of the investigator(s).

- Unlike HFACS, the RCA process used in healthcare is not highly structured. Investigators generally choose where to look, and report against broad headings. This leads to a lack of consistency in investigation processes and reported findings, and hence a lack of comparability in reports even across the same organisation.

- ‘Root causes’ are often poorly identified, specified at a high level and are not actionable. For example, I’ve seen a fair few reports where the root cause was the error itself. ‘Poor communication’ is a common catch-all ‘root cause’ that doesn’t help to develop a response.

- RCAs have contributed to a culture of blame, with much of the focus on ‘who in the front line did what’, rather than on how the organisation is shaping front line action, what safety systems are missing, or how safety systems have failed. This is a result of the relatively unstructured nature of healthcare RCAs – and also of the culture of healthcare organisations, which my next bullet point addresses.

- Unless they are prompted to do so, RCA investigators tend not to investigate failures that arise in the upper echelons of their organisation. They often take for granted everyday vexations (e.g. shortage of qualified staff), so these do not appear in reports. And they rarely advance solutions that are truly systemic (e.g. a strategic approach to workforce planning). This may be because investigators suspect that the upper echelons of their organisation don’t want to hear about contributory factors at higher levels, because ‘everyone surely knows’ that staffing is an ongoing problem that no one can fix. On the other hand, the upper echelons will want to know which front line professional did what wrong, because that appears to be easier to fix (in the short term at least). The upshot is that an organisation’s cumulative RCAs end up providing a very skewed account of the issues that are undermining safety.

- In most organisations, each RCA stands alone and the corrective actions proposed are specific to the incident under review. This tends to result in a patchwork of partial and inadequate fixes.

‘Old fashioned medications’ By Ruth Hartnup, CC BY 2.0

As Benjamin Franklin, Mark Twain, Albert Einstein, Rita Mae Browne, and Chinese proverbialists are all reputed to have said, a person who does the same thing over and over again expecting different results is deluded. The RCA ‘cure’ is unscientific and it isn’t working.

So exactly how could HFACS make a difference?

In a 2021 research publication in Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management Isherwood and Waterson compared the usability and utility of HFACS with a well-established alternative, AcciMap. They concluded “this review suggests HFACS has the most supporting evidence and may be the most implementable…the recommendations generated would offer patients a safer, higher performing, healthcare system”.

HFACS ensures that investigators consider all four levels of influence and causation, pay attention to organisational systems, and resist assumptions that the person nearest in time or proximity to the error is to blame. Using the framework facilitates consistency in investigations, so that you can get a comprehensive data-led understanding of system safety.

With HFACS you can build a simple database that enables you to view trends, compare departments, divisions and sites, prioritise your safety efforts, and monitor the effectiveness of your interventions. You can also use HFACS proactively to assess risk.

If you’re already excited by the prospects for HFACS you could scroll down to the bottom and get in touch with me. But I do want to say something here about why good investigations are more than instrumentally important.

HFACS and the moral imperative of a good investigation

When something goes wrong in healthcare, everyone agrees that ‘lessons must be learned’. But we need to understand why this is so important to patients or service users and their supporters, and also to professionals involved in adverse events. It is morally important because it is part of making sense of what has happened, rebuilding trust and making amends.

Avalokitesvar, the bodhisattva of compassion

Wellcome Library, London. http://wellcomeimages.org CC BY 4.0

First, for people who have been injured, the process of making sense of events is part of the process of coming to terms with them. We owe an account to people who trusted us and have been injured by our actions. We have to look fearlessly at what went wrong, and give them an honest explanation. Even if you agree with experts such as Hollnagel (see below) who argue safety is built on looking at what goes right, as well as what goes wrong, there will always remain a moral need to explain what happened.

Second, I believe that when patients say ‘make sure this cannot happen to someone else’ they are not just being altruistic. They are also operating on the principle of ‘Archbishop Tutu’s pen’. I describe this in my post on apology. The Archbishop explained that if you steal my pen, apologise, but do not return the pen, the apology is worthless because nothing has happened. So, being truly sorry means doing something to repair the injury. In the case of patient harm, you cannot ‘give the pen back’. The harm was done and it cannot be undone. But you can do something else. You can prevent it happening again. To do this, your investigation has to be sufficiently robust to support quality improvement activity.

Third, it is worth remembering that professionals involved in adverse events are also profoundly affected by them. They too have a strong moral need to make sense of what happened. They want to understand the roles they and others played, and they want to think about how they can metaphorically ‘give the pen back’.

Finally – HFACS and “Safety II”

Some argue that Reason’s model is being superseded by newer approaches to understanding error. In my view, the differences are sometimes exaggerated. Erik Hollnagel and others argue that to develop safer systems we have to learn from what goes right, and not just from what goes wrong. (This talk by Hollnagel at Risky Business is a good introduction to his thinking.) Hollnagel is not suggesting that we should give up trying to understand from what goes wrong; only that we also need to find out how people manage to make things go right.

HFACS can help with this too. The framework is a valuable safety audit tool that can help you locate ‘gaps’ in your safety processes before harm occurs. And using it to look for what is working well in parts of your organisation helps to build and sustain resilience across the whole.

Find out more

The basic HFACS framework is freely available to view, but the nanocodes that make it a useful tool are not. I have modified existing nanocodes to make them suitable for use in the NHS, and I share these with providers. Moreover, you do have to know how to use HFACS to get the best value from it. I have been trained by its developers.

If you would like to talk about how to do better systems-based investigations consistent with the NHS’s Patient Safety Incident Response Framework do get in touch.

In addition to Isherwood and Waterson’s article two other publications describing the application of HFACS in the healthcare setting are worth reading. One reports using HFACS to analyse surgical never events while another reports its use more widely across a health provider system. You can also read up on HFACS in Shappell & Wiegmann’s book A Human Error Approach to Aviation Accident Analysis