Ethics in NHS Integrated Care Systems

I am privileged to provide support to a variety of NHS ethics forums. An interesting new development is the small but growing number of groups serving Integrated Care Systems.

I am working with the Dorset ICS to develop their new ethics forum, and one of the reasons for this post is to find out about the work others may be doing, to share knowledge, and to contribute towards building a community of practice in this area.

The UK Clinical Ethics Network has given valuable support to ethics committees within NHS provider organisations for the past twenty years. Many new ethics groups came into existence (even if only briefly) during the pandemic. It is difficult to keep details up to date, but at the last count UKCEN listed 42 provider organisations with an ethics forum. There are fewer regional groups, but some, such as that in Devon, have developed system wide advice during the pandemic and may continue to do so after it.

The pandemic has brought home the importance of providers working together in health systems, sharing hard won insights, and adopting common approaches to difficult ethical decisions. There is clearly an appetite for continuing our system wide ethical conversations as ICSs start to establish themselves.

An interesting challenge for the ICSs will be to build a shared understanding of what may constitute an ‘ethical issue’ concerning their system, and to develop nuanced approaches to thinking about them together.

One of the aims for the ICSs is to plan and provide care that attends to population health and health inequalities. The ethical questions are therefore going to be different from those concerning individual patients, which have tended to be the main focus of ethics committees in provider organisations. And the questions are likely to be wider ranging than the ongoing dilemmas around allocating resources, questions that have long been central to the work of Clinical Commissioning Groups.

So what is ‘being ethical’ at ICS level likely to involve? By way of example it could, in the way the pandemic has, involve choices around the design of public health interventions such as vaccination programmes. It might involve deciding between interventions that serve everyone, and interventions that have greater benefits for groups that have been historically underserved. There could be questions about how best to meet the concerns of both young people and the adults who care for them, when there are different views about what is acceptable. It may involve reviewing the credibility of long term social programmes that cannot be subject to randomised control trials, and will therefore will never yield hard evidence of their effectiveness. It could be about how to prioritise spending on buildings or on digital technologies across an ICS, now that this capital expenditure is no longer purely a provider decision but co-ordinated by the ICS. These are only initial thoughts about what might arise, and it will be intriguing to see what starts to emerge as groups take and encourage referrals.

David Seedhouse 3rd edition

What resources might members of ICS ethics groups draw on as they start to work together? I have developed a framework for Our Dorset, which I will share here once it is approved

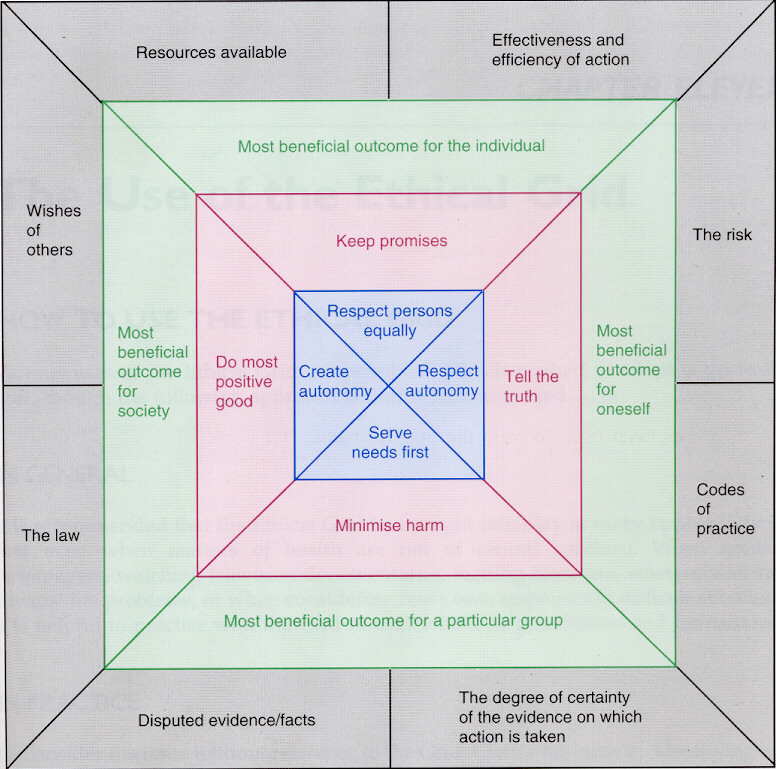

Those familiar with David Seedhouse’s ‘ethical grid’ will be able to see its influence on the framework I have developed. Seedhouse’s grid is an admirable means of organising ethical thoughts around the kinds of complex choices that health and care entail. The grid was published in his book Ethics – The Heart of Healthcare over three decades ago, and has been a useful guide to generations of students and professionals. The grid is, as he noted in the preface to the first edition “not a calculating machine.It is merely a euphemism for ‘ethical reflection’. It can produce different solutions to the same situation dependent upon who is using it…”.

So what is the value of a grid, or something like it, if it does not produce easy conclusions? There are several ways to answer this, but for me the most important reasons for having a visible reference framework are these:

- that it helps diverse groups (of clinicians, managers, public participants and so on) to converge on a shared language for articulating ideas and disagreements;

- it encourages a conscientious search for valid reasons to settle an issue in a particular way;

- and it supplies a framework for giving a clear account of those reasons to those who have an interest in the outcome of deliberation.

In addition to drawing on Seedhouse’s framework I have also used a very helpful article by Georg Marckmann and colleagues ‘Putting public health ethics into practice: a systematic framework’ (available on open access at Frontiers in public health 3 (2015): 23.)

Pending permission to post the Our Dorset ethics framework, it would be good to hear from others who may be working in this area. Please get in touch via my contact page and maybe we can start sharing ideas.

In the meantime, this is David Seedhouse’s grid.

Seedhouse’s ethical grid, from Ethics – The Heart of Healthcare